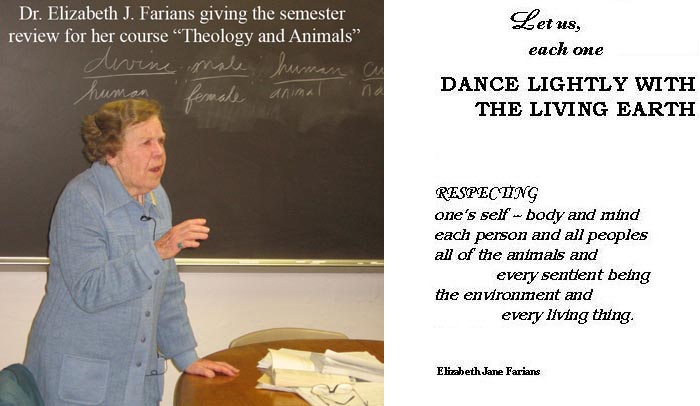

About Elizabeth J. Farians, Ph.D.

April 10th, 1923 - Oct 21st, 2013

A Bio by Mary Ann Lederer

I first met Elizabeth Farians on a picket line protesting the U.S. War against Iraq. We soon met again at Ulysses, Cincinnati's only vegetarian restaurant in the '90's. Elizabeth was dining with a very good mutual friend, Rev. Maurice McCrackin, who had become a vegetarian as a result of Elizabeth's convincing testimony. As I got to know Elizabeth, we often discussed our philosophies of life, and she won me over to some new ways of thinking. I told her that if she would write the essence of her beliefs in a few words or lines, I would illustrate it. And so together we made the poster:

"DANCE LIGHTLY WITH THE LIVING EARTH

Respecting

one's self--body and mind

each person and all peoples

all of the animals and every sentient being

the environment and every living thing"

Because of Elizabeth, I added to my own repertoire of respect for all human beings, the belief that we must cherish every being -- not just humans-- but all of life and the planet. We must do this if we are going to survive.

Recently when I told Elizabeth that I would like to nominate her for the McCrackin Peace and Justice Award, I interviewed her extensively. An amazing story unfolded of an incredible person with an incredible life.

Elizabeth Farians is a woman of uncompromising strength and convictions combined with a profound sensitivity and gentleness. She has strength of character, gentleness of soul. She spent a lifetime as a pioneer and leader for women's rights, for changes in the Catholic Church, for human rights, and for the rights of all beings. She has a relentless drive for justice. What distinguishes Elizabeth Farians is the breadth of her vision. She sees the connectedness of all the human rights issues: poverty, racism, war, feminism, the animals and the earth. A commitment to non-violence demands a life style which embraces all these concerns.

Her childhood began in poverty and today at age 75 her life is one of frugality and voluntary simplicity. She won a lot and lost a lot and she survives. With great honor and pride I nominate my friend and teacher, Elizabeth Farians, for the 1998 McCrackin Peace and Justice Award.

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH

Elizabeth Farians developed an integrated girls' swimming program in Cincinnati before swimming was racially integrated.

She became an umpire before women were umpires.

She started the first athletic program for Catholic girls and women within the Archdiocese of Cincinnati. She started the first racially integrated parish leagues for girls' activities while boys' leagues remained segregated. She started a girls' program which was adopted nationally by the Girl Scouts.

She was one of the first women to study theology and to become a theologian in either Catholic or Protestant religions. She was one of the first women to teach theology in Catholic colleges. Even before Vatican II she worked toward changing the roles of Catholic women. She integrated the Catholic Theological Society.

She assisted Frances McGillicuddy in starting the first St. Joan's International Alliance in the United States.

She pulled together Protestant women ministers and Catholic women and started the Ecumenical Task Force on Women and Religion which became the Task Force on Religion of the National Organization for Women (NOW).

She was on the first board of NOW. She founded and headed the first Task Force on Religion of NOW.

She was involved in the civil rights movement, the March on Selma, Alabama, and other civil rights activities. She was involved in the anti-war movement.

She was and is an advocate of free speech.

She appeared on the Phil Donahue Show as a theologian discussing "Women and the Priesthood."

She testified before both Houses of the U.S. Congress as a theologian providing information in support of the Equal Rights Amendment.

She lectured all over the country before women's groups to awaken women to their rights in the Church.

She gave the baccalaureate address at Brown University, speaking as a theologian on feminism. She was the first woman to speak from the pulpit at Brown University Chapel.

She started three chapters of the National Organization for Women: in Hartford, Connecticut; at Mt. Clair College in New Jersey; and in Cincinnati. She started the first NOW chapter in Ohio.

She started a free university women's studies course at Loyola University, one of the first women's study courses. She wrote and presented a number of papers on aspects of feminism, on over-population, on the roles of women.

She participated in a national protest against Bell Telephone Company to get better wages and opportunities for women.

She started the Joint Committee of Organizations Concerned About the Status of Women in the Church. She met with Bishop Bernadine (later to become Cardinal Bernadine).

She organized a protest referred to as the "national unveiling" protesting that women always had to keep their heads covered in church.

She organized a protest called "pink and ash," sending ashes wrapped in pink ribbons to the bishops. The ashes were the remains of Instruction 66, a liturgical law that gave lay men a wider role in the liturgy but excluded women.

She and the Joint Committee met with the committee of bishops.

She filed a complaint with the Department of Health Education and Welfare, the first complaint of sex discrimination filed in higher education in the U.S..

She led a delegation of eight NOW members who met with Governor Gilligan and asked him to support the ratification by Ohio of the Equal Rights Amendment. They also asked him to create a department of women with paid positions to deal with women's problems.

She met with Senator Tom Luken and convinced him to co-sponsor the ratification in Ohio of the ERA, which he did.

She brought the first Women's Political Caucus to Ohio.

Her case against Loyola University became the title case in a large class action suit.

She led a demonstration of women at the University of Cincinnati to get the university to have a women's studies program. She and members of NOW and Women's Liberation 'sat in' at the Arts and Sciences Dean's Office.

She worked with Mac on the death penalty issue. She started the Cincinnati Chapter of the Ohio Coalition Against the Death Penalty.

She picketed and protested many times when Mac and Ernest Bromley were arrested.

She wrote and obtained a grant for $15,000 for a lecture series on the death penalty and organized monthly lectures.

She was treasurer of an ad hoc peace group dedicated to preventing the Bromley's house from being seized by the IRS.

She has been actively involved in the animal rights movement and the vegetarian movement in such groups as: Mobilization for Animals, the Animal Rights Community (ARC), the Cincinnati Vegetarian Society, the Vegetarian Resource Group, and EarthSave. She has distributed petitions against leg holdtraps and petitions to save the doves. She has demonstrated against turtle races, circuses, rodeos, animal testing, factory farms, and P & G product testing.

Elizabeth Farians

ROUGH DRAFT

by Mary Ann Lederer

Elizabeth Farians was born in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1923, an only child of parents of Irish-German Catholic decent. The Farianses were very poor and Elizabeth recalled a time when all their belongings were put out in the street, and they had to move into the basement of friends. Sometimes food was scarce, and Elizabeth was always prepared to quit school and get a job to help her family. The pressure of poverty led her to complete high school and college each in three years.

Beginning in childhood, Elizabeth was frustrated by the restrictions placed on her because she was a girl. She was determined to do anything she wanted that boys did in spite of the obstacles. She became committed early to changing the roles of women and the images women had of themselves. Throughout her entire life she was a pioneer in the struggle for the right of all women to develop their fullest potentials.

Elizabeth was imbued with a deep love of nature and an almost unique affinity for animals. As a child she learned the birds, trees, and wild flowers indigenous to this area. Her concern for nature has been a life long passion.

Elizabeth attended Catholic elementary school but switched to public schools in high school and college. As a child her main focuses were athletics and religion, although she excelled academically and earned money tutoring other youths in Latin and geometry. She graduated from Withrow High School and received a Bachelor's Degree in Physical Education and Masters in Administration of Education from the University of Cincinnati.

Elizabeth was very athletic, won medals in many sports, and became a certified umpire in softball, track and field, basketball and volleyball. Very few women were umpires at this time. She was on the National Olympic Committee for track and field.

While attending the University of Cincinnati in the early 1940's, Elizabeth was hired to develop a Physical Education program for delinquent girls at Girls' Town which was run by the Good Shepherd Sisters. Long before public swimming was racially integrated, she insisted on integrated swimming. The Recreation Commission opened a pool for the Girls' Town girls on Saturdays and allowed Elizabeth to run the program as she wished.

After graduating from the University of Cincinnati, Elizabeth taught physical education at Our Lady of Angels High School in St. Bernard; however she aspired to eventually teach teachers. She felt this would be the most efficient way to bring about the changes she envisioned -- the empowerment of women.

She became interested in encouraging young women in team sports. At a time when society and especially the Catholic Church pressured girls to avoid strenuous activity and to focus on having babies, Elizabeth's views were quite novel and radical. She began to promote her philosophy and beliefs that women can compete in everything in life and that team sports can teach them to do this. She believed that team sports would promote leadership in women. She opposed the rules in women's sports which often restricted the development of women's abilities.

Elizabeth got a job in a small Catholic college, St. Mary of the Woods in Indiana. It was very difficult for a Catholic woman to get a job teaching in secular colleges, but she eventually obtained a job in the Physical Education Department at Eastern Illinois State College.

While at Eastern Illinois State, Elizabeth organized and played basketball for the Schmidt Jewelers team of the Amateur Athletic Union of America. While she was captain of the team, the Schmidt Jewelers won the state title. When Eastern State College officials found out, they ordered her to quit her extracurricular sports. She refused, but left Eastern and eventually returned to Cincinnati.

In need of a job, Elizabeth went to the Catholic Youth Organization of the Archdiocese of Cincinnati and requested she be hired to start a girls' athletic program. She became director of a girls' and women's program which she initiated. She remained head of this program for five years.

During that time she started a Girl Scout program in which girls could earn special church related medals. The program was similar to that of the Boy Scouts. The Girl Scouts went along with the program and eventually it became a national program.

The job of director of the girls' program for the Catholic Youth Organization involved organizing a large number of parish teams. Since the Catholic churches in Cincinnati tended to be either all black or all white, the boys teams were automatically either black or white. Leagues were formed based on location, so black teams mostly made up black leagues. Hence, boys' sports were segregated based on the locations of the churches.

When Elizabeth started the girls' leagues, the same segregated system again began to fall into place. Around that time Elizabeth met Father Dominic Ferrara, a Verona priest who had lived in Sudan, Africa, and now was pastoring the Holy Trinity Church on 5th Street in Cincinnati, a church with a mostly black congregation. Father Dominic told Elizabeth that he opposed the racial segregation of the teams. Elizabeth agreed and proceeded to reschedule and rearrange all the girls' leagues so that they would be integrated. So the girls' leagues never were segregated as the boys' leagues were. The teams themselves, of course, remained segregated as long as the church parishes were mostly either all black or all white.

Then Father Dominic asked Elizabeth to help his girls' team, and Elizabeth became the team's volunteer coach. Elizabeth had an enormous work energy and commitment, and she spent many extra hours on the job.

Father Dominic was a very popular priest, and he became a Bishop. He and Elizabeth remained good friends until he died recently.

Always proud of her Roman Catholic heritage, Elizabeth became interested in Catholic education, in philosophy and theology. She began taking night classes in downtown Cincinnati from Xavier professor Dr. Herbert Schwartz. She became fascinated with Thomas Aquinas, the official theologian of the Roman Catholic Church. Through Dr. Schwartz she learned of a new graduate program for women at Saint Mary's Notre Dame College in South Bend, Indiana, where for the first time Catholic women were able to receive graduate degrees in theology.

And so Elizabeth entered Saint Mary's Notre Dame with the intent of working for a Ph.D. in Theology and the hope of teaching it on a college level.

Before this time, Catholic women had never been allowed to study theology. Sister Madeleva Wolfe, President of Saint Mary's Notre Dame, believed that nuns would make good teachers of religion. She petitioned the Pope for permission to start a graduate school of theology for women. Unexpectedly the Pope granted her permission.

At that time there were no women theologians in either Catholic or Protestant Churches. Sister Madeleva's program was not a religious education school. It was a theological school that taught the works of Thomas Aquinas and other Catholic scholars and thinkers. This marked an enormous turning point in the Church.

At Saint Mary's Notre Dame most of Elizabeth's classmates were nuns; however, one lay woman, Mary Daly, became her good friend. (Mary Daly has since authored many books and has led the way as a progressive theologian and eventually as a radical feminist.) She and Elizabeth remain friends today.

Unlike the nuns in her classes at Saint Mary's, Elizabeth had to work her way through school. She paid her tuition by working as Sister Madeleva's private chauffeur and by teaching classes at the college.

All of this happened prior to Vatican II and perhaps to some extent helped pave the way for the restructuring that was about to follow.

It became increasingly clear to Elizabeth that religion was the root of misogyny. She realized that as a theologian she could help women tremendously by challenging the Church's oppressive teachings and practices.

When Elizabeth received her Ph.D. in 1958, jobs in her field were hard to get. Most dioceses would not consider a woman to teach theology. However, Elizabeth managed to land a temporary job at Cardinal Cushing College in Boston. When the job at Cushing terminated, she was hired to teach at Salve Regina College in Newport, Rhode Island. Again the job was temporary. She replaced a nun who had gone back to school. When the nun returned, Elizabeth was offered a job teaching physical education.

Although Catholic colleges began to open up and allow women to take courses in theology and biblical studies, women were still not permitted to teach these subjects. Only priests could teach philosophy or theology.

Following Salve Regina College, Elizabeth was hired at the University of Dayton, a Marinist Catholic university. She got the job because a priest had suddenly left his teaching position. Elizabeth agreed to teach philosophy for a year if they would then allow her to teach theology, given she proved herself to be a skilled teacher. On the first day of class several young men walked out when Elizabeth entered. Nonetheless, things went well, and she became known as a good teacher. After two years teaching philosophy, Elizabeth approached the provost, the priest who had hired her and reminded him of their agreement. Could she now teach theology? she requested. His reply was simply: "Get out. You're fired!" Several male faculty members wrote letters and protested on her behalf, but in this system the provost makes the decisions, and so Elizabeth left Dayton.

Elizabeth's next job was at Sacred Heart University in Bridgeport, Connecticut in the mid '60's. The Viet Nam War was going on; the women's movement had not yet begun; and Elizabeth was teaching theology.

She applied for membership in a theological organization, the Catholic Theological Society. Only a short time before, the society had begun to include not just priests but lay men. Father Charles Curran had submitted a proposal that anyone with a proper theology degree could join; hence, Elizabeth received a membership card. However, when she went to her first meeting, a banquet at a convention in Providence, Rhode Island, she was refused entrance. The priest at the door threatened to call the police if she didn't leave and attempted to push her to the elevator, and she threatened to call the press. Just then Father Curran came along and insisted they let her in. She was of course the only woman there and probably the only woman in the organization.

Sacred Heart University at Bridgeport, Connecticut was a co-ed lay Diocesen college near the women's Albertus Magnus College, a Dominican school in New Haven, Connecticut. While at Sacred Heart University, Elizabeth was invited to be on a panel at Albertus Magnus College to talk about the role of women in the Church. Her inclusion on this panel was probably the result of her friendships with some Protestant women ministers. These women ministers invited her to give a speech to their organization, the New England Ministers Association.

The main speaker on the panel was Father Bernard Haering, C.S.S.R., a renowned European liberal theologian. He had recommended changes to the Vatican Council. He believed women could be priests but this had to be done gradually. On the panel, Elizabeth criticized Haering for being too conservative. Her criticisms and her remarks about his "lamentable gradualism " were recorded in Catholic newspapers which were read all over the country. And so by the mid '60's Elizabeth had become known as a leader in a barely begun women's movement and the Church.

In the early '60's, Elizabeth joined St. Joan's International Alliance, a suffragette organization of Catholic women which had its origins in England. The group oppossed white slavery and atrocities such as genital mutilation but was careful not to oppose the Catholic Church.

Frances McGillicuddy became the representative of St. Joan's in the United Nations. Elizabeth met Frances McGillicuddy and helped her start the American Section of St. Joan's International Alliance.

When the St. Joan's group was so reluctant to criticize the Church, Elizabeth pulled together the Protestant women ministers and along with Catholic women started the Ecumenical Task Force on Women and Religion (around 1965). Elizabeth planned for the Task Force to become a national organization, and in a way it did. However, the National Organization for Women (NOW) started and Elizabeth brought the Task Force into NOW.

In October 1966 Betty Friedan and a group of women met in Washington DC and officially started NOW. These women had come to Washington to a national conference of women from state commissions working on women's issues. These Commissions on the Status of Women were voluntary groups under the Department of Labor. Some of the women at the conference were frustrated by the inactivity and ineffectiveness of the commissions. Betty Friedan, Dr. Pauli Murray, and others committed themselves to action and not just talk and became the founders of N.O.W..

There was a notice in the New York Times stating that a new group had just formed with Betty Friedan as the leader. Elizabeth saw the notice and called Betty Friedan immediately. Betty came to Bridgeport where she and Elizabeth met in a bar and Betty invited Elizabeth to join NOW. Elizabeth told her about the Ecumenical Task Force and they discussed adding a Task Force on Religion to NOW. Soon Elizabeth was a member of the national board of NOW and the head of the Task Force on Religion.

One of the women on the newly formed board was Dr. Catherine Clarenbach of the University of Wisconsin. She was head of the Wisconsin Commission on the Status of women under the Department of Labor. Betty Friedan was elected first president of NOW and Catherine Clarenbach became the vice president.

Elizabeth had become imbued with the Catholic Worker philosophy. She met Dorothy Day, founder of the Catholic Worker, and attempted to get her involved in the feminist movement. Dorothy Day had previously been a feminist and imprisoned for supporting the suffragettes, but her priority had become issues of poverty and peace.

While at Sacred Heart, Elizabeth was active in the civil rights movement. She decided to join the march to Selma, Alabama. Her friend, Father Clement Burns, was chaplain at Yale and teaching at Albertus Magnus College. He asked Elizabeth to drive a group of students from Yale to the march. The marchers were told to be very careful during their drive to Alabama. There were "safe houses" on the route where they would be given directions and assistance on where to go. They drove without lights through farm lands from one safe house to another until they arrived in Selma. The people of Alabama were unaccustomed to seeing integrated groups of northerners and could cause them serious trouble.

Selma was one of Elizabeth's early encounters with the Rev. Maurice McCrackin, who would become her very good friend.

Elizabeth also became involved in the anti-war movement where she met Father Daniel Berrigan, renowned peace advocate, who has been arrested many times for his anti-war activities. Father Berrigan introduced her to David Miller, a man who had burned his draft card. Father Berrigan asked Elizabeth to arrange for David Miller to speak at Sacred Heart University, which she did. A riot almost ensued. Students were enraged that a man would burn a draft card. Elizabeth calmed the students, stopped the near riot, but lost her job in the process. She was fired perhaps for her connections with Father Berrigan, her opposition to war, her feminism, and her outspokenness on the panel when she challenged Father Bernard Haering, all of which earned her a rather radical reputation. She finished teaching the semester in theology and once again returned to her home in Cincinnati.

Around 1968 Elizabeth was hired in New Jersey as chaplain in the Job Corps which was run by the YWCA. This job lasted less than a year because the Job Corps was down-sized. However, living close to NewYork was convenient. Elizabeth participated actively in New York NOW and started a NOW chapter in New Jersey.

The New Jersey Chapter of NOW met at Mt. Clair College where Elizabetth taught for one semester. Mt. Clair wanted her to stay and teach physical education, but she wanted to seek jobs teaching philosophy or theology.

During her time on the east coast, Elizabeth was often written about on the New York Times front page. Edward Fiske, the religion editor, called her frequently and regularly. Elizabeth lectured all over the country before women's groups about women and the Church. She spoke before Congress. While in Washington DC, she met Alice Paul and members of the National Women's Party (the original suffragettes). Alice Paul lived at Belmont House near the Capital. Elizabeth and Alice Paul became good friends. Paul, who had been the leader of the Suffragette Movement, had been imprisoned in 1920, force fed when fasting, and fasted until women were granted the right to vote. Dr. Alice Paul authored the Equal Rights Amendment which she and a small group of women introduced at every Congress. Then a Congressman named Emanuel Sellers would kill the bill every time.

Alice Paul saw hope that Elizabeth would bring changes for women in the Catholic Church, and in truth Elizabeth has.

Around 1970 Elizabeth appeared on a panel on the Phil Donahue Show in Dayton, Ohio. The topic: Women and the Priesthood.

Also around this time Elizabeth was invited to give the Baccalaureate address at Brown University. She was the first woman to speak from the pulpit in the Brown chapel. She was invited because Charles Colson had been indicted as part of the Nixon Watergate conspiracy, and he was unable to attend. The wife of the president of Brown had become a feminist and wanted Gloria Steinem to replace him; however, Steinem was considered too radical. When the chaplain from Brown invited Elizabeth, she assured him that she was more radical than Steinem. Apparently he felt that Elizabeth, a Catholic theologian, could not possibly be that radical.

And so Elizabeth gave a cut and dried feminist speech which shocked and upset the parents and faculty but pleased many of the students. The audience gasped at comments like, "The only thing that women and men cannot do interchangably is wet nurse...." The speech was taped and played by the college radio station.

Elizabeth went to Washington DC many times and testified before both Houses of the U.S. Congress in behalf of the Equal Rights Amendment. She spoke as a theologian contending that the ERA did not violate religious doctrine.

Elizabeth always came home between jobs and during summers. She stayed at her parents' house. Her parents were no longer poor. Her father worked 60 to 70 hours a week as a repair welder. His work was steady and his wages had gotten better.

Finally Elizabeth was hired to teach theology at Loyola University in Chicago. Once again she was hired to replace a priest who had walked off the job. She was one of the first women in the United States and particularly one of the first lay women to teach theology. (Mary Daly taught theology at Cushing College before Elizabeth did.)

Elizabeth started three chapters of NOW. While teaching in Bridgeport, Connecticut she started a NOW chapter which met in Hartford. She started a chapter in New Jersey while teaching at Mt. Clair. And she started Cincinnati NOW, the first NOW chapter in Ohio, during the summer of 1969 while she was teaching at Loyola.

In Cincinnati, Elizabeth met Maggie Quinn. Elizabeth called the first meeting of NOW, but then had to return to Loyola. At the second meeting, Maggie Quinn was elected president. While at Loyola, Elizabeth continued to work with Maggie Quinn and Cincinnati NOW.

At Loyola, Elizabeth was a popular teacher. In addition to teaching theology, she developed an extracurricular Women's Studies course on feminism, taught in a coffee house. She invited many lecturers such as Betty Friedan, Dr. Catherine Clarenbach, and Dr. Naomi Weinstein. This was a free university course which was a popular vehicle for teaching at that time. The free courses were the result of students, frustrated by the inappropriateness of much of their curricula, requesting that faculty members teach them subjects that interested them.

Also at Loyola Elizabeth wrote many news releases and a number of articles. She was invited to present a paper to the American Academy of Religion at a conference in California. The title of the paper was: "Phallic Worship - The Ultimate Idolatry." Unfortunately Elizabeth never got to the conference; she became ill and ended up in the hospital.

Elizabeth presented a paper to an organization concerned with negative population growth. She contended that overpopulation is creating a major ecological problem and that if women had more role options, they would have fewer babies. Her article was entitled "Ethics, Population, and Women." While her concept is well accepted in many circles today, it was quite innovative at the time she presented it.

Elizabeth started The Joint Committee of Organizations Concerned About the Status of Women in the Church, an umbrella group in which NOW's Religious Task Force was a member. The Joint Committee attempted to get the Bishops to listen to the concerns of women. Elizabeth met with Bishop Bernadine, then head of the Catholic Conference of Bishops (later to became Cardinal Bernadine) and asked him to arrange a meeting between the Joint Committee of women and the Conference of Bishops. Bernadine refused to arrange the meeting.

After several years of trying unsuccessfully to meet with the bishops, she organized a demonstration in Detroit where the Bishops' Conference was taking place. In the demonstration referred to as "pink and ash," ashes were wrapped in pink ribbons and sent to the bishops. The ashes were the remains of Instruction 66, a liturgical law that gave lay men a wider role in the liturgy, but excluded women.

Eventually, in 1970, the bishops did meet with the women from the Joint Committee. The bishops agreed to set up a commission to study the problems that the Church had with women, and they are still studying. This was an historical meeting, the first time the bishops had met with non-bishops.

Elizabeth referred to the many efforts of the Joint Committee to communicate with the Bishops as "bishop badgering."

Elizabeth was an excellent teacher, but once again her politics got her in trouble. She was called into the theology department and told, "If we'd known you were a feminist, we wouldn't have hired you."

There was a strike on her behalf. Loyola students, mostly men, who were protesting the Viet Nam War, added Elizabeth to their protest. There were petitions, a letter writing campaign, and protests, partly encouraged by psychology Professor, Dr. Naomi Weinstein. Nonetheless, in spite of popular support, she was fired.

However, before she left Chicago she worked with Mary Jean Collins-Robson and the newly formed Chicago chapter of NOW. Chicago became the national office for NOW. Elizabeth and Mary Jean helped organize a protest against national Ma Bell Telephone Company because of the low wages and lack of opportunities for women.

As head of the Task Force on Religion, Elizabeth and other NOW members from Chicago went to Milwaukee for the "national unveiling," protesting that women always had to keep their heads covered in church. Father Joseph Wamser of St. John De Nepomuc Church had stated that he wouldn't give communion to women whose heads were uncovered. On Easter Sunday in 1969, women from NOW's Religious Task Force removed their bonnets at the alter. The priest did give them communion, but then he angrily threw their hats on the floor.

Some of the major activities of the Task Force focused on the Catholic Church because Catholic women were so angry about the way women were treated in the Church. Under the direction of Elizabeth, the Task Force carried out any number of demonstrations aimed at getting the Bishops to deal with the low status of women in the Church. They burned newly promulgated liturgical documents discriminatory to women and sent the ashes to the Bishops with a poem entitled “Pink and Ash”. Protesting required head covering, they took off their fancy Easter bonnets and placed them on the alter rail while receiving communion at the Easter Sunday High Mass in what was called “The Easter Bonnet Rebellion”. The local leader of this event received a death threat. Working with Alice Paul, Elizabeth lobbied for the Equal Rights Amendment and she testified for the Amendment before both the U.S. House and the U.S. Senate. In her testimony Elizabeth stressed the principle that true religion is always empowering and never oppressive. This was surely damning because for many years, the Catholic Bishops had opposed the Amendment in whatever way they could, sometimes speaking out against it and by getting their house organization, the National Council of Catholic Women to oppose it. Even so Elizabeth tried to get a meeting with National Council of Catholic Bishops to present the case for women’s equality. When their request continued to be ignored the Task Force escalated their request, picketed the Bishops’ meeting and put out Elizabeth’s news release, “We Will Be Silent No Longer”. Finally the Bishops relented and a process began whereby the Task Force met with a liaison committee of the Bishops and presented them with a list of demands to bring women into equality in the Church. This was an historic meeting, August 20, 1970, the first time, as far as is known, that the Bishops ever meet with non-bishops. All these events made national news and probably reached all the way to the Vatican.

Not long before Elizabeth was fired from Loyola, a new law barring sex discrimination was added to Title VII of the Civil Rights Act. Elizabeth filed a complaint with the Department of Health Education and Welfare. This was the first complaint of sex discrimination ever filed in higher education in the United States. Elizabeth had to work continuously to keep the case active in HEW.

“If I had known you were a feminist I would not have hired you” said the Jesuit Chair of Theology at Chicago’s Loyola University, Rev. Mark Hurtubise, when he fired Dr. Elizabeth Farians, pioneer woman theologian, veteran feminist and prominent NOW member. What had she done?

Now Elizabeth had become known as a whistle-blower. She was 47 years old and had been fired from many jobs. She couldn't get references. Young women with Ph.D.'s began getting the teaching jobs in theology for lower salaries. She did, however, eventually get a small settlement from Loyola.

Around the same time she was fired from Loyola, her friend Mary Daly was fired from Boston College. Similarly, students and faculty protested in Mary Daly's support. Also other academic institutions in the Boston area were supportive, and the Administration reconsidered. Dr. Daly was reinstated.

Mary Daly then initiated a Women's Institute within the Boston Theological Institute. Elizabeth was hired to develop and direct it. The Women's Institute was a consortium of theological schools in the Boston area. However, a year later Elizabeth's contract was not renewed, and she returned to Cincinnati again.

By this time the Equal Rights Amendment had been passed by the U.S. Congress. Passage by thirty-eight states was now necessary. Back in Cincinnati, Elizabeth continued to work on ratification in Ohio. She led a delegation of about eight NOW members who met with Governor John Gilligan and asked him to support the ERA. They requested Gilligan create a department of women with paid positions, such as a Status of Women Commission, under the Department of Labor. The woman Gilligan eventually appointed was not really a feminist, and she did little to advance the cause of women.

Elizabeth and NOW members met with Senator Tom Luken in a bar, where they encouraged him to co-sponsor the ratification in Ohio of the Equal Rights Amendment, which he did.

Elizabeth was a member of the National Women's Political Caucus started by Bella Abzug. Around 1970 or '71, Elizabeth organized a meeting of the Women's Political Caucus, bringing together Ohio's politically active women to promote women as candidates for political office. The meeting was held in Columbus and was the beginning of the first Women's Political Caucus in Ohio. In 1972 a group started in Cincinnati. Last year, 1997, the Cincinnati Chapter of the Women's Political Caucus celebrated its 25th anniversary. Local women such as Ann Sayre, Joan Kallman, and Kathy Helmbock were honored for their participation in the first Cincinnati chapter of the Women's Political Caucus; and Elizabeth was also honored for initiating the first chapter of the Caucus in Ohio.

And so Elizabeth brought both NOW and the Women's Political Caucus to Ohio. Perhaps she could rightfully be called the Mother of Ohio Feminism.

Meanwhile Elizabeth spent many years fighting her case with Loyola. She took many approaches and a great deal of time. She went to the Department of Health Education and Welfare. HEW found grounds for a suit under the new sex discrimination laws but found it difficult to enforce the civil rights law in religious affiliated colleges. The new law was more easily applicable to schools receiving more federal funding. HEW had little jurisdiction over Catholic schools, except for threatening to cut their small grant monies. Over the years the turnover of personnel at HEW was great, and Elizabeth had to explain her case over and over to new people working there. Eventually the frustration became discouraging.

However, several national organizations did actively support her case, among them:

NOW's Legal Defense Fund, the National Education Association, and the American Association of College and University Professors, which was the first to join in support of her.

HEW was directly involved because Elizabeth's case was in the education field. The original complaint was filed by HEW. Also the Equal Employment Opportunities Commission (EEOC), under the Department of Labor, became involved because the EEOC had jurisdiction over Title VII of the Civil Rights Act. Elizabeth was working with two government departments which didn't always work well together. And there was little HEW or EEOC could do because they had little leverage over religious schools.

Also, a private organization in Washington DC was looking for sex discrimination cases. This organization asked Elizabeth to allow them to take her case and use it as the title case in a class action suit. Glad to get the legal help, she agreed. However, the group found more and more cases to add to their suit and eventually Elizabeth's case was lost in the shuffle.

Elizabeth finally obtained a small settlement from Loyola by herself. Her case somehow got lost in the bureaucracy of the government departments. What she had always wanted was to get her job back, and that never happened.

Elizabeth tried relentlessly to find employment. Fighting her case and looking for jobs became full time. She developed a women's studies program for colleges and universities and presented it to the University of Cincinnati. Her proposal was rejected. The University of Cincinnati was not ready for or open to a women's studies program. So the local chapters of NOW and Women's Liberation came together in protest. They stormed the University's Arts and Sciences College and peacefully held the Dean, Dr. Crockett, captive in his office for several hours. Women with baby carriages walked up and down Clifton Avenue demanding child care. This was precipitated by the Dean's refusal to speak with women who were feminists.

Elizabeth had been the leader of the protest. Eventually the University of Cincinnati did accept a women's studies program, though Elizabeth, of course, was not hired to head it. And the woman who was hired was not really a feminist.

In Cincinnati in the early '70's, Elizabeth became involved in the political activities of the Reverend Maurice McCrackin - Mac. Mac suggested she work with him on the death penalty issue. A small group met in Mac's church.

In 1973 the Supreme Court made some major changes in the death penalty law. Under the new regulations, states could not execute prisoners until they had rewritten their state laws to conform with the new federal laws. Many people on death row were moved to "population," which was a good thing. However, Mac had the foresight to realize that the executions could begin again once the states had met the new requirements.

Elizabeth started the Cincinnati Chapter of the Ohio Coalition Against the Death Penalty. As chaplain, Mac was actively visiting prisoners all over Ohio. Attorney Alan Brown debated often against the death penalty. When Mac was arrested frequently for his political positions, Elizabeth worked with Alan Brown to get him out of jail. Elizabeth was once permitted to visit Mac in jail by telling the officials that she was a theologian; they thought she was a chaplain.

Many times when Mac and his friend, Ernest Bromley, were arrested for a variety of causes, Elizabeth picketed and protested until they were released.

One time, two prisoners escaped and went to hide at Mac's house. He had befriended them in jail. Although they stole his car, he refused to cooperate with authorities to assist in their capture. Hence, the judge ordered Mac's arrest for obstructing justice.

Before the sheriff arrived to arrest Mac, Mac called Elizabeth to come to the church and be supportive of him. While they waited, Lou Moore, writer for the local newspaper arrived. As the sheriff and some very large men entered, Mac slumped down and became non-violently uncooperative. The men carried him out. Elizabeth felt that the presence of Lou Moore helped inhibit the roughness of the sheriff's men. When all had left, Elizabeth locked up the empty church and went home.

Elizabeth met and sometimes worked on the death penalty issue with Rose Maynard, lawyer from Columbus, Ohio, who has spent many years helping prisoners on death row.

Around 1977, the Ohio Coalition against the Death Penalty began meeting at the Friends' meeting house on Winding Way. Elizabeth became involved writing a grant for a lecture series on the death penalty. Her grant brought $15,000 requiring another $15,000 in matching funds, though the matching funds could be in building space or time and not only in money. Elizabeth arranged a lecture every month on the death penalty, each lecture at a different location -- the University of Cincinnati, Xavier University, St. Peter in Chains Cathedral, St. Mark's Church.

One of the monthly lecturers was the renowned Dick Gregory, black comedian and philosopher. The event was held at St. Mark's Church, where there was a predominantly black congregation. The result was a large turnout of people wanting to hear Dick Gregory. However, Gregory did not show up. The audience was upset and seemed to feel that Dick Gregory's name had been used simply to get a big crowd.

In desperation Rose Maynard, advocate for fair treatment of prisoners, got up and began talking about the prison situation and the death penalty. Maynard worked so closely and sensitively with prisoners and was such an effective public speaker that she won the audience's approval and the event was a success.

Elizabeth continued her activities in the peace movement working with Ernest and Marion Bromley. The Bromleys had not paid taxes in many years, always keeping their incomes below the level requiring taxes. Elizabeth became deeply involved in the effort to prevent the IRS from taking the Bromleys' house. Meetings were held on the second floor of Arnold's Cafe. Elizabeth was the group's treasurer. The group did everything possible to save the house. Public pressure was on the Bromleys' side, and they eventually won the right to continue living in their house.

No longer employed, Elizabeth began to garden. She lived frugally, growing organic vegetables to eat. By about 1970 she had become a vegetarian; she became vegan around 1980. She joined new organizations, but rarely held major positions of leadership any more. Animal rights organizations had started and she immediately became actively involved. She distributed petitions against leghold traps and later petitions to save the doves. She has protested turtle races and all abuses of animals. She demonstrated against circuses, rodeos, animal testing, factory farms, P & G product testing. She took her dog, Cindy, to a P & G protest wearing a sign that said: "Do not test on me." The Associated Press photo of Cindy became widely publicized.

In the early '80's, she joined Mobilization for Animals which became the Animal Rights Community (ARC). She persuaded ARC to have vegetarian potluck dinners. This sparked the formation of the Cincinnati Vegetarian Society.

Elizabeth invited Mac to ARC and introduced him to vegetarianism, which he immediately embraced.

Around 1994 Elizabeth and Mary-Jane Newborn developed a program on the effects of dietary choices on poverty and presented it at the Celebration for Human Rights held at the Mt. Auburn Presbyterian Church.

Elizabeth continues to participate in protests on a variety of issues, sometimes initiating the protests herself but often joining in demonstrations. At age 75, Elizabeth was the full-time caregiver for her 95 year old mother. She has been doing this increasingly over a 10 year period.

Elizabeth's commitment evolved. She began as a reformer of Catholicism, of Christianity, as a feminist, then an advocate for human rights and civil rights, a proponent of peace, of free speech, an opponent of the death penalty, a vegetarian and environmentalist, a friend and ally of animals, of all beings, of all life and the planet. She sees the connectedness of the issues, the connectedness of us all, the sacredness of life. Her view is inclusive and heart felt.

In conclusion: Elizabeth Farians is a woman of uncompromising strength and convictions combined with a profound sensitivity and gentleness. She has strength of character, gentleness of soul. She spent a lifetime as a pioneer and leader for women's rights, for changes in the Catholic Church, for human rights, and for the rights of all beings. She has a relentless drive for justice. What distinguishes Elizabeth Farians is the breadth of her vision. She sees the connectedness of all the human rights issues: poverty, racism, war, feminism, the animals and the earth. A commitment to non-violence demands a life style that embraces all these concerns.

Now at 86 (2009) she remains as firey and persistent as ever as she presents the connection between feminism and animals.

by Mary Ann Lederer

Above text is copyright Mary Ann Lederer 2008 and may not be used without permission. Request it by emailing her at maryannlederer@gmail.com